The Effect of Wingspans on Shooting and Offensive Proficiency

- Bruin Sports Analytics

- Dec 14, 2021

- 9 min read

By: Anthony Rio

In the past decade, wingspans have become all the rage in the NBA. Particularly, starting with the John Hammond-constructed Milwaukee Bucks in the early 2010s, the general manager who infamously drafted a skinny Greek teenager with a 7’3” wingspan who would change the franchise as well as the landscape of the NBA for years to come.

The logic of drafting a player with long arms is pretty simple: the longer a player's arms are, the more space they can cover, the more passing lanes they can get their hands in, and the closer they can vertically get to the basket. Another perk a player with a long wingspan possesses is that their added size doesn’t come at the cost of less mobility and lateral quickness, like a purely taller player with longer legs would normally face. In targeting players with long wingspans, the theory was that this would obviously bolster a team's defense solely based on physical characteristics- a “longer” team would never be physically overmatched or dominated.

In general, this line of thinking was pretty spot on. Just look around the league right now at the game's best defenders: Giannis Antetokounpo, Draymond Green, Kawhi Leonard, Rudy Gobert. Of course, all of these players are on a different level physically and mentally which separates them, but for all of them their 7’3”+ wingspan plays a part in separating them. When considering this, I wondered why every team doesn’t target these players similarly to how the Bucks did if it guarantees better defensive outcomes.

Looking at that 2013 Milwaukee Bucks team in Giannis’ rookie year, there was a clear lack of shooting. I also thought about some of the best shooters in the NBA in recent memory and realized that a lot of them had shorter wingspans relative to the average wingspan for their respective heights. The greatest shooter ever in Stephen Curry (6’4.5” wingspan), last year's leading three point shooting rookie Desmond Bane (6’4” wingspan), and recently-retired all-time great three point shooter JJ Redick (6’3” wingspan) came to mind as great shooters with below average and shorter wingspans. These thoughts spark the question of whether wingspan and arm length have any correlation to overall jump shooting ability or shooting ability in specific scenarios.

When considering other sports such as golf, this sport has a swinging motion rather than shooting motions. However, the logic still applies and follows such that a player with longer arms and a longer swing might be able to hit the ball with more power, yet have less control than a player with a shorter swing and wingspan. In golf, longer arms and thus a “longer swing” can more easily lead to less control of where the ball will be hit due to the idea that the more parts and pieces there are to a swing, the more that can go wrong, thus a more condense swing is more consistent and reliable. Though it has been proved that in broad terms a jump shot with more arc will more often go in the hoop, and a player with longer arms could generate more power into a shot, shooting is all about accuracy not distance; all about muscle memory and repeating a motion that works, which physically speaking is easier to do when the motion is quicker and more condensed, giving shorter armed players an advantage.

To answer this of wingspan vs. shooting I looked at the shooting data from players who have played in 500 or more minutes in any of the last 5 full NBA regular seasons. I examined this data in relation to a player's “length” which I defined as a player's height minus the given player's wingspan. I compared players in this fashion because in general NBA players who are taller are worse shooters and less skilled, in part because of the way they are trained their entire lives, thus comparing players by their “length” equals the playing field. For context, the average player in the NBA over the last five seasons for players with over 500 minutes is approximately 6’6.25” with a 6’10.6” wingspan, equating to a length of +4.35”.

I chose to look at certain shot types by range and context. The most easily comparable statistic is free throw percentage because these shots are from the same distance each time with no defense, and have the least amount of external factors besides the player's shooting ability. Looking at “pull-up” off-the-dribble jump shots versus “catch-and-shoot” attempts provides insight into whether or not a players jump shot has versatility and a wingspan affects a jump shot translating from the simplest stand still, no dribble form to a more difficult and reactionary, yet less robotic circumstance.

When comparing shooting ability between players, the most equitable comparison is free throw shooting, where the distance and undefended nature of the shot remains constant, so the difficulty of the shot does not vary. Data was only used for players who shot 25 or more free throw attempts in their 500 or more minutes on the floor to filter out unreliably small sample sizes. In each of the five years included in the analysis, the regression line of the plot showed slightly negative correlation between “length” and free throw shooting percentages, meaning that in general the lesser a player’s length was, generally the better free throw shooter they were. Of all the relationships between a shooting metric and player “length”, free throw percentage was the strongest as they had the most “negative” and steep slope with an average yearly r-squared value of 0.01967599. It is the closest statistic to a universal general shooting metric because it has the least amount of variation in the conditions of each attempt, making it the most reliable statistic.

For 3PT shooting there was also a slightly negative correlation and an average yearly r-squared value of 0.01195671 for all given seasons of data between 3PT% and “length”. So again, generally speaking if a player’s “length” is smaller, they are likely a better shooter.

The other two types of shooting metrics used are corner 3s and long two point jumpshots (between 16 feet and the 3PT line). Of all spots on the floor, midrange and long twos are the most unassisted and off the dribble jump shots, whereas corner 3s are the most often assisted and catch-and-shoot looks. For both of the data subsets used, outliers that wouldn’t exist given a shot attempt minimum were taken out. Specifically, the minimum percentage for both midrange and corner 3s was 15%, while the maximum was 55%. Both of these numbers were selected to ensure that only sustainable percentages for each of these types of shots were included in the data used. For corner 3s there was a slightly “negative” relationship with player length (average yearly r-squared of 0.00911991), meaning that if a player’s length was greater, generally their corner 3PT percentages were a bit lower.

However, for “long two” jump shots between 16 feet and the 3PT line, there was the least correlation of all the shooting metrics looked at. This shooting metric was the only metric such that there was no slight “negative” correlation between “length” and long two shooting percentage in all five seasons of data looked at. Though it is difficult to pinpoint why this is, one possible explanation is that because “long twos” are the most likely type of jump shot to be a pullup (off the dribble), unassisted, and self created caliber, only very good shooters are usually wanted and allowed to take these traditionally more difficult and less efficient shot (on a points per possession basis). As a result, only the upper tier of shooters, regardless of wingspan or length, have “long twos” in their shot diet and put up a reasonable volume of them.Thus, having overwhelmingly only the upper echelon of shooters in the population of the data might throw off the slight trend we had been seeing in the other shooting metrics.

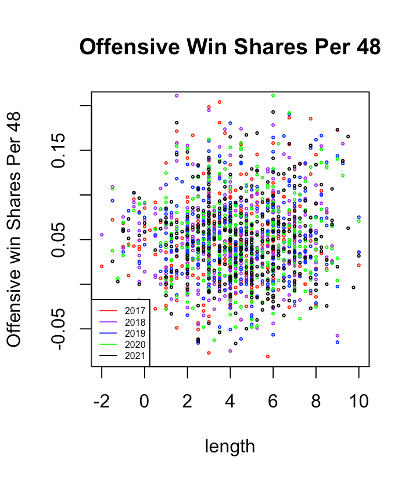

To try to further my exploration into the impact of players length on their jump shooting ability, I looked into whether or not this slight advantage in jump shooting ability that players with shorter wingspans relative to their height had led to improved offensive impact. Traditionally, shooting ability is the most valued commodity in the NBA because the better shooting ability a team and its players have, the more efficient each shot and offense in general is. In addition, teams who can shoot jump shots at a higher clip force their opposition to sag off of off-ball players less, spacing the floor more to make drives and shots inside the arc easier and more efficient, as the paint is less clogged up with help defenders. To generalize each player's offensive impact, I used two “at large” statistics, one being Offensive Box Plus Minus (OBPM) and the other being Offensive Win Shares Per 48 Minutes (OWS per 48). OBPM measures how many points added on the offensive end a given player adds per 100 possessions while accounting for the players who are on the floor with them. OWS per 48 is a statistic that looks at how much a player's offensive impact correlates to one win over the course of a full 48 minute game.

I compared and plotted with regression lines both of these statistics to a respective player's “length” and didn’t find any trends. In essence, the slight shooting advantage detected with players with shorter wingspans relative to their height did not materialize in an increased offensive impact and effectiveness. For both stats and graphs, there was weak “positive” correlation for a few of the regression lines but not all, and the data was definitely not definitive one way or the other.

This relationship between shorter armed players with an increased shooting ability not having an increased offensive impact could be a product of many factors. It’s hard to know, but in theory one of these factors could be that players with smaller “length” are worse finishers around the rim because simply put, they’re further away from and below the rim when trying these shot attempts.

The last thing I looked at was whether or not any correlation between shooting ability was more or less present based on players positions. I separated the players into three positional groupings, based on their labeled position (via Basketball Reference). If a player was listed as either a point guard (PG) or shooting guard (SG), they were put in the “guard” category. If they were labeled as a small forward (SF) or power forward (PF), they were set in the “forward” bin. Lastly, if a player was identified as a center (C), then they were a part of the “center” data subset. To investigate the slight trend found in shooting ability positionally, I specifically looked into overall 3PT percentage, FT percentage, and corner 3PT percentage.

Positionally, when comparing players length and free throw shooting percentage, guards, forwards, and, and centers all showed a slight negative correlation. However, centers were by far the worst free throw shooters, and guards were clearly the best. In addition, the center data was the most spread out.

Corner 3PT shooting yielded similar results to the free throw shooting data for guards and forwards, where both groups showed a slight “negative” correlation between having length and shooting ability, as well as guards being better shooters than forwards. The center data displayed a more noticeable trend between smaller length and increased 3PT shooting ability, however the center data is less reliable because the data was of a smaller volume, and also much more spread out.

Lastly, 3PT shooting data split up positionally from the last five seasons showed a slight “negative” relationship between length and 3PT shooting for all position groups. Again, we see that the data varies more in the center's positional category in which we also see less data points.

In conclusion, positions don’t have much of an effect on how extreme the small trend between a short length and better shooting ability. The only takeaway from this data is that in general guards are the best at shooting whereas centers are the worst. This makes sense logically due to the fact that traditionally guards are more perimeter oriented players, and therefore have better perimeter skills and are more comfortable shooting from further away from the basket. Conversely, centers are normally more inside-oriented, therefore spending less time on the perimeter and being less comfortable and efficient shooting from distance away from the rim.

Overall, after looking after the last five seasons of shooting data, players with shorter wingspans relative to their height did end up generally proving to have a minuscule advantage in shooting ability on 3PT shots, corner 3s, long twos, and free throws. Long twos, the most often off-the-dribble jump shot, showed the smallest trend between shooting ability and length, potentially a product because normally only the upper tier of shooters take this type of shot at a reasonable volume. There was still a slight trend shown in all of the shooting data, so it did not matter where the jump shot was being attempted from or how it was being shot (off the dribble, catch-and-shoot, or standstill), players with shortest “length” had a slight leg up in shooting ability generally. However, this shooting advantage for shorter armed players did not manifest into a them having a greater offensive impact and being a better overall offensive player than players with longer “length”.