World Chess Championship 2024: How one mistake decided a world champion

- Bruin Sports Analytics

- Apr 1, 2025

- 12 min read

By Billy Peir

The 2024 World Chess Championship, held from November 25 to December 12 in Singapore, Was one of the most exciting world chess championships in recent history. The challenger, Gukesh Dommaraju, is a young indian prodigy who won the fabled Candidates, beating out other top competitors like Hikaru Nakamura and Fabiano Caruana for the chance at the crown. At the young age of 18 years old, Gukesh would become the youngest undisputed world champion ever. The defending champion, Ding Liren, was one of the few chess players to ever reach a 2800 FIDE rating, an official rating by the chess federation of a player’s skill. Ding had recently beat Ian Nepomniachtchi for the title of World Champion in 2022, winning in tiebreakers after tying 7-7 in classical matches.

In the end, Gukesh defeated Ding by a score of 7.5-6.5, winning on the final game of the series, with the black pieces, to become the youngest world champion in the history of Chess. This article delves into a comprehensive analysis of the 2024 World Chess Championship, examining key statistics, game strategies, and pivotal moments that defined this historic match.

The Competitors

The Challenger: Gukesh Dommaraju

Gukesh Dommaraju made waves when he won the Candidates Chess

tournament in April, defeating much higher players like Fabiano Caruana and Hikaru Nakamura for the right to challenge for the title of World Champion. At the time of the match, Gukesh was 18 years old, one of the youngest to challenge for the title and would be the youngest to win it. At a global FIDE rating of 2783, Gukesh was ranked 5th in the world at the time of the world championship. If he were to win, it would mean a golden age in chess for India, inspiring the next generation to come.

The Defender: Ding Liren

The reigning world champion, Ding Liren from China, defeated Ian Nepomniachtchi in 2022 to become the World Champion. Known colloquially as “Ding Chilling”, a play on words for the Mandarin term for ice cream and Ding’s cold, calculated playstyle, Ding was many the favorite to win this match and defend his title. At the time of the match, Ding was rated 2728, 23rd in the world, a huge dropoff for a player who was recently rated over 2800. However, he had not played in almost any official matches for the entire year leading up to the match, leading many to question his form entering the match.

The Opening

As most chess players know, the opening moves are the most explored and theorized part of the game. At a high level, players spend countless hours preparing and theorizing on the first 10 or so moves of the game. At a chess championship level, strategy has changed from choosing the most popular openings and the most popular variations of the openings in favor of choosing less “optimal” openings that are less explored and lead to more variance.

This pattern was shown early in this championship. Only 4 of the 14 games played were started by the move e4, moving the pawn in front of the king 2 squares. This has been by far, the most popular opening since the start of chess. In fact, only 4 more of the games were started by the move d4, by far the second most popular starting move, moving the queen’s pawn two squares.

Ding Liren, a player most known for playing two main lines: The Queen’s Pawn Opening and corresponding variations such as the Queen’s Gambit, the Catalan, and the Nimzo-Indian as the white pieces, and the Marshall Defense in the Spanish as the black pieces. However, for this game, he definitely switched it up.

With the black pieces, Ding played the French Defense in 3 of the 7 games. This opening was surprising, as mainstream theory evaluates this defense strategy as outdated due to the lack of space that you give yourself, allowing your opponent to take control of the majority of the board, leading to claustrophobic positions. However, he managed to bring new ideas into an outdated opening that allowed him to draw 2 games and even win one game.

With the white pieces, Ding chose a variety of openings to explore, but he used the London System twice. This opening is seen as extremely boring at a high level, as it allows black to “equalize” or for white to lose their opening advantage very quickly. In addition, Ding also played the English Opening twice, starting with the move c4, twice. As one of the more unusual openings, it did allow Ding to catch Gukesh and win in one of the two games he played with it.

Gukesh, on the other hand, chose to play around a couple of main strategies. With the black pieces, he didn’t have much choice as Ding played openings that forced Gukesh to adapt to what he played. However, Gukesh explored ideas within those openings that often forced Ding out of his preparation.

With the white pieces, when Gukesh did not start with the move e4, which Ding played the french defense, Gukesh played some variation of the Catalan, an opening that Ding helped popularize, using a fianchettoed bishop on g2 to pressure the center of the board and utilizing the flank pawn on c4 in the Queen’s pawn opening, in 3 of the other 4 games. He set it up in many ways, starting with the Queen’s pawn once and starting with the move Knight to f3 twice. Gukesh won one of these 3 games, proving his opening preparation.

Rarity and Preparation

In terms of preparation, Gukesh was by far the riskier and more prepared player with the openings. To analyze this, I used 3 main statistics: Popularity is the average popularity of each move. If in a known position, someone plays the most popular move, it receives a popularity score of 1. If it’s the 2nd most popular move, it gets a 2 and so on. Rarity is the percentage of people who play the move from a position. A move that 12% of players play from that position gets a rarity score of 12%. These numbers are compiled in a Chess Database that stores the games of thousands of chess games by rated players. I used the database Chessbase.com.

As you might be able to tell, Gukesh played rarer moves, with an average popularity of 1.34 to Ding’s 1.23, as well as an average rarity of 67.7% compared to 68.26%. However, this doesn’t give us a lot of insight into who actually came out of the opening phase victorious.

Timing and Evaluation

There are two main ways to evaluate the success of a phase like the opening phase. The first is the evaluation, which evaluates who is winning on the board. Chess uses a points system where each piece is worth a certain amount, such as a pawn, which is worth 1 point. The evaluation of a board state is evaluated based on these. Typically, an identical position but white is up a pawn will lead to a board evaluation of +1 in white’s favor. But if black has a fork that will win a rook the next move, black will have the advantage. Evaluations are typically rounded to the nearest hundredth of a point, so an advantage of 0.01 is 1% of a pawn. I also use a metric called Win Probability Lost, or WPL.

Time advantage is another way to evaluate success. The world chess championship is played in a format where players have 2 hours to make their first 40 moves, and then after, they get an extra 30 minutes plus 30 seconds for every move they make subsequently. If players time out, they lose. However, losing on time isn’t the only threat: being low on time gives players less time to think and more chances to miss key ideas and blunder. A great way to keep track of this is using Time Advantage, or how many minutes (or seconds) a player is ahead of the other player.

So who played better in the opening, Ding or Gukesh? Let us examine the stats:

As you might be able to tell, Gukesh had the advantage in both time and evaluation. On average, Gukesh left the opening phase up 0.08 in evaluation and a whopping 24 minutes ahead of Ding. A big pattern was Ding spending a LOT of time in the opening. He spent more than 30 minutes on 4 moves in the opening, which for a format that allows 3 minutes per move on average, takes a 4th of the time away for 1 move. With the black pieces, it was exceptionally worse for Ding: Gukesh left the opening with a comfortable average lead of 0.35 and a time advantage of 40 MINUTES. With Ding’s white pieces, it was at least better: the lead was cut down to 0.2 and only 8 minutes down on average.

The Mid Game

Clearly, Gukesh massively outplayed Ding in the opening. However, entering an unknown position is an extremely different game. Here, players have to think on their own, out of their preparation, and to put it simply, play chess. Pure intuition, calculation, and nerves will determine who outplays the other in the midgame.

Unlike the opening, there isn’t a lot of analysis to be done besides who played better, so instead, I will highlight some of the biggest moments in the midgame.

Game 1: Gukesh Vs. Ding 0-0

In game 1, down two pawns and desperately trying to avoid a losing endgame, Gukesh launches an attack with his two bishops, queen, and rook as a last resort. However, surgical and methodical, Ding responds by consolidating his pieces, trading rooks, and finding the clutch move e5, the only move that works in the position, cutting off the diagonal of the dark-squared bishop and forcing it to retreat. Ding went on to win this game after stopping all possible checks, starting the series off with a win with the dark pieces.

Game 3: Gukesh vs. Ding 1-2

After being bombarded with Gukesh’s prep, Ding takes a risk and tries to sacrifice a bishop in order to split Gukesh’s pawns and consolidate the position. However, in his calculation, he misses a crucial move: instead of taking the knight with his bishop, Gukesh plays a backwards knight move, Ne2, that puts Ding under immense pressure. Faced with a losing position and a massive time disadvantage, Ding crumbles and loses on time, equaling the score at 2 apiece.

Game 11: Gukesh vs. Ding 5-5

Facing massive pressure on the A file by Gukesh’s two rooks, Ding attempts to defend everything by moving his queen backwards to allow his rook on e7 to defend the b7 pawn. However, he misses the move Queen takes, which wins Gukesh the game instantly. If Ding takes with the pawn, Rook to b8 takes a rook and pins the queen to the king, winning a knight. If queen takes, then bishop takes queen and you can’t take with the pawn because of the same rook to b8, leading to Ding resigning shortly after, giving Gukesh the lead.

Game 12: Ding vs. Gukesh 5-6

Back against the wall, Ding needs a win in the next 3 games to tie, and he executes in a huge fashion. After playing an English opening, Ding puts the squeeze on Gukesh, winning 2 pawns early and creating a passed pawn on the D file that becomes impossible to defend. The nail in the coffin is the rook sacrifice, rook takes e7, that leads to a brutal Mate in 7 that involves Ding’s queen on e3 and the eventual promoted pawn working in tandem to unleash a devastating checkmate, leading Gukesh to resign on the spot. This clutch game ties the series at 6 with 2 games to go.

Who won the midgame?

So, who actually won the midgame? Both players won 2 games in the midgame, so by record, it was tied. In terms of time and evaluation, let us look at the statistics:

By all metrics, Ding clearly crushed the midgame. His greater expertise and confidence shown in the midgame, allowing him to equalize many bad positions and time advantages. After being down an average of 0.08 after the opening, Ding managed to flip the script and exit the mid game phase with the advantage. In addition, after being down for more than 40 minutes with the black pieces, Ding managed to bring the time advantage to about equal, and even gained a 3 minute time advantage with his own white pieces. Ding showed that he was the reigning world champion for a reason. Now it will come down to the Endgame.

The Endgame

The endgame occurs when all pieces are traded and each player is left with 2-3 major pieces and pawns left. In endgames, precision is key, as one bad move can lose you the game instantly. We won’t go into much depth about the statistics in the endgame: Ding and Gukesh drew every single endgame except for one. In those games, since all of the games ended at an evaluation of 0, there is not a lot of significance in time advantage or evaluation, as it does not matter anymore.

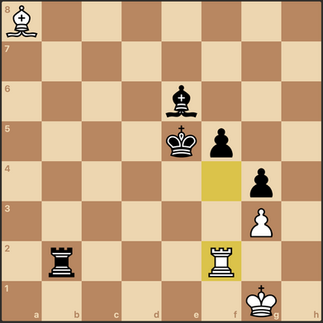

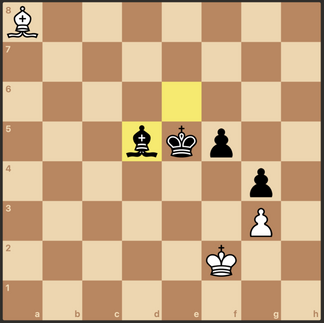

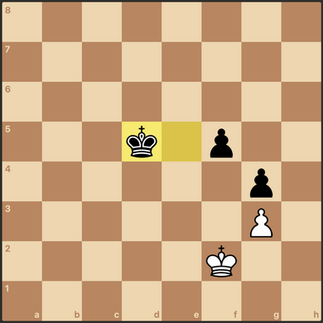

Game 14: The Decider

Tied 6.5-6.5, Ding entered the game with the white pieces against Gukesh and the black pieces. Ding opted to go with a King’s Indian opening. After a relatively uneventful opening and midgame, the game enters an endgame of rooks and bishops with Gukesh up a pawn. Although Gukesh is up a pawn, this is a drawn endgame as the pawns are all on the same side. This is Gukesh’s game to play for a win, but there aren’t many winning chances with two top players.

After marching his pawns down the board, Gukesh manages to trade one pair of pawns. The game is still completely equal and should be an easy draw. However, neither player is willing to accept a draw as it is the last game before tiebreakers.

The Blunder

The position is completely equal. However, in this position, Ding plays the move Rook to f2, offering a trade of Rooks.

Gukesh obliges, and then trades bishops as well, leading to a 2 on 1 pawn endgame. However, after Ke3, Ke5, Kf2, Kd4, Ding resigned as you cannot stop both pawns, giving Gukesh the match, set, and game, making him the youngest world champion in history. Simply put, it was a simple misevaluation of the pawn endgame. Ding thought that the 2 on 1 was a draw, but he was simply wrong, leading to a heartbreaking loss for Ding.

Overall

So, who actually played better? While Gukesh won more games than Ding, did he actually play better? We can start by analyzing the statistics.

First, we can analyze the evaluation throughout the tournament. Another way to analyze accuracy besides the evaluation at a particular state is to calculate the evaluation lost per each move. While the best move loses 0 evaluation, worse moves might lose anywhere from 0.01 evaluation to as much as 3 or 4 in a single move. Below is the total evaluation lost throughout the entire game, not including opening moves.

While Gukesh won more games, Ding arguably played the more accurate chess throughout the entire match. He lost less evaluation throughout the match and lost less evaluation per move. Although the difference is only a mere 2 points of evaluation, less than a bishop or knight, it is significant enough to question if Gukesh was actually the better player. However, this is only one statistic.

Another popular way that the main website for chess, chess.com uses to analyze games is by move classification. This classifies moves according to a number of descriptions, ranging from Best, the best possible move in the position, to Blunder, a move that is a huge mistake, to Brilliant, a Best move that is also a sacrifice and hard to see. The move types, from best to worst are classified as Brilliant, Great, Best, Excellent, Good, Inaccuracy, Mistake, Miss, and Blunder. Miss is slightly different from a Blunder in that instead of making a mistake, you fail to see a winning move that has the same effect as a Blunder. The Move distributions across the 14 games are shown below.

While this graph might be hard to analyze, there are a couple of trends here. First, Gukesh found the best move at a higher rate than Ding. However, Ding and Gukesh had approximately the same amount of “strong” moves, moves that aren’t inaccurate or worse. While Ding had 7 more inaccuracies than Gukesh, Gukesh also had 4 more mistakes than Ding. Finally, Ding had the only 3 blunders of the match.

A way to evaluate this graph is through Win Probability Lost, or WPL. WPL is a rough estimate of how much “win probability” a player loses. The best move in a position does not lose any chances of winning, so the WPL is 0. The second best move might lower one’s winning chances by 1%, so the WPL is 0.01, and a huge blunder might lower the winning chances by as little as 0.3 or as much as the entire game.

Throughout the 14 games, Ding lost about .5 more of a game than Gukesh did, which makes sense, as Gukesh did win the match. What is interesting to note is that even though Gukesh lost more overall evaluation, he lost less win probability. This means that although Gukesh was more inaccurate overall, his mistakes were certainly a lot less impactful than Ding’s. What stands out is Ding’s 3 blunders, which completely changed the course of each game.

Summary

In summary, the 2025 World Chess Championship was a story about composure in critical situations. Gukesh showed the depth of his opening preparation through his off-tempo openings that made Ding get to early positional and time squeezes. However, as the game left known territory, Ding showed why he is the reigning world champion through his precise defensive play, bringing many games back to equal and putting pressure on Gukesh to win games. However, in the most critical positions, Gukesh kept his composure better, while Ding made a couple of costly mistakes that cost him several games, and eventually the match.

Comments