Quarterback Mobility and Longevity

- Bruin Sports Analytics

- Apr 1, 2023

- 6 min read

By: Chinmay Varshneya

Introduction

In American Football, the quarterback is the leader of the offense, and they traditionally facilitate production through passing. But, with time, a greater emphasis has been placed on a quarterback’s ability to make plays in more ways than one. We can thus introduce some terminology. Less mobile quarterbacks are generally referred to as pocket passing or pro-style quarterbacks. Current examples include Matt Stafford and Joe Burrow. They traditionally stay within the pocket, which is the area formed by the offensive linemen when guarding the quarterback, and they throw the ball from there. They rely on accurate passing to make plays.

This can be contrasted with mobile or dual-threat quarterbacks. These quarterbacks are generally quicker and more athletic than their counterparts. They are able to make plays with their legs as well. Current examples include Josh Allen and Lamar Jackson. These players’ athletic potential and dynamic play-making ability are attractive to many coaches. They allow coordinators to call a much wider variety of plays and they add another layer of complexity to the offense.

Thus, teams embrace players that can both throw the ball and run - whether it be on a designed play or even to simply extend time a pass when protection breaks down. However, this can come at a cost. Traditionally, quarterbacks are coached to slide and avoid contact. The NFL even has specific rules to protect quarterbacks in the pocket which are not extended to other offensive players. However, when scrambling or running, passers lose this protection and are treated as ball carriers. Therefore, it logically follows that they are more likely to take bigger hits and to put themselves in harm's way.

Research Question

This article will analyze the lifespan and effectiveness of more mobile quarterbacks and therefore look to see if they perform as well in the long term as pocket passing quarterbacks. This is especially topical due to the turbulent nature of Lamar Jackson’s contract talks as well as the pre-draft hype placed on Florida prospect Anthony Richardson. Understanding the career trends of mobile quarterbacks will help provide a valuable perspective to both of these stories.

Quarterback Trends and Examples

As an introduction, we will first look to understand how past careers of dual-threat quarterbacks have panned out. It’s easy to pick out examples of injury-plagued mobile quarterbacks such as Robert Griffin III, who ultimately had a short career in the league, however, it is more illuminating to look at examples of players that had relative longevity to better understand how their performance changes over time.

Starting with a player that leads active mobile quarterbacks in games started, we have Russell Wilson.

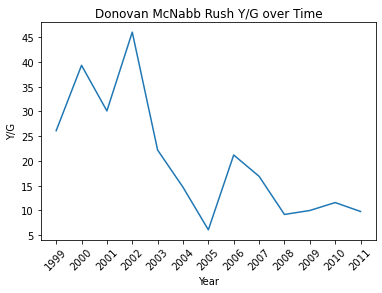

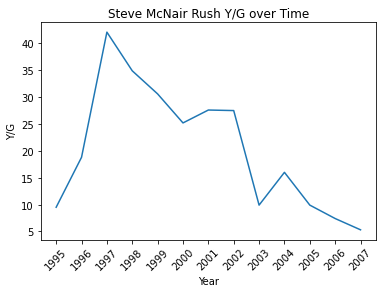

We can see a clear trend in which his rush yards per game have dropped off as he spends more time in the league. Even though he has had no major injuries throughout his career, it appears that simply the impact of age is turning him from a quarterback that at one point averaged over 50 rushing yards a game to one that struggles to average more than 20. When looking at notable dual-threat quarterbacks from the past 20 years such as Steve McNair and Donovan McNabb, a similar trend appears. It is worth noting that in addition to age, however, McNabb and McNair also faced several injuries. Injuries are obviously a major causal factor when looking at a player’s lack of mobility. This is one of the reasons why running backs are known to have such short lifespans in the NFL. As a result, some may attribute this decrease in rush yards per game back to McNabb and Mcnair's dual-threat playstyle.

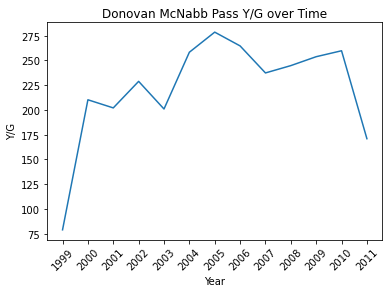

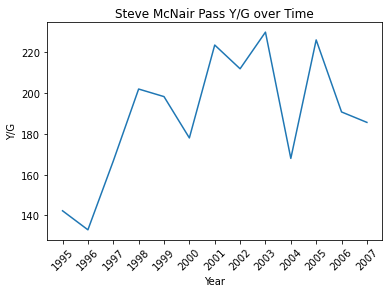

It is important to note, however, that these players were starting quarterbacks for over 10 years in the NFL. For those wondering how they were able to keep their job despite a drop off in rushing performance- look at their passing.

Their passing performance per game follows a completely opposite trend to that of their rushing. As their careers progressed both players seemed to become more prolific passers. This implies that they were able to compensate for their worsening mobility with better passing. Using this, we can make a generalization that NFL quarterbacks that lose mobility, generally due to injury and age, can remain impactful if they improve their proficiency as pro-style quarterbacks.

For further context, we can look at the top 10 QB rushing seasons of all time.

The graph looks at the age of each of the quarterbacks during their record-breaking seasons. As indicated by the legend, the dotted red line marks the average age of quarterbacks with at least 2 starts in this year (it is around 28.4 years old). See that all the quarterbacks are below the average age for a starter when they have their historically productive season on the ground. Clearly, mobile quarterbacks perform best at younger ages.

When it comes to our question regarding lifespan and performance over time, we also need to better understand if mobile quarterbacks suffer more injuries than their pocket-passing counterparts. We can approach the question with the graph below.

Mobility and Injury

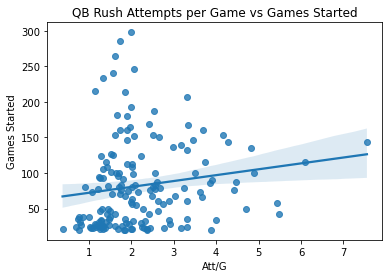

Nearly all injuries in the NFL are the result of contact so by looking at how many times a quarterback is tackled by a defender in the backfield, we can better understand if the amount of abuse they take is correlated with their mobility, which we measure by rush attempts per game. The straight line shows that clearly, no such relationship exists and therefore it is unlikely that more mobile quarterbacks will have more collisions with defenders. One possible reason for this is that while their mobility does lead to them getting tackled more, it also makes them more evasive. Therefore, they can scramble away and avoid pressure on a play whereas a less mobile quarterback might have been sacked. Thus their evasiveness may “cancel out” the additional hits they take from running on other plays. If this is the case, the number of hurries for mobile quarterbacks should still remain high. Looking at the relevant graph gives the expected results:

So while mobile quarterbacks might face more pressure than their pocket-passing counterparts, that does not translate into them actually getting tackled more. This result makes it difficult to conclude that dual-threat quarterbacks get injured more than pro-style ones.

Career Length

Still it is likely that a more mobile style of play introduces more wear and tear on the body. Furthermore, we have already demonstrated that it is generally difficult for dual-threat quarterbacks to stay productive on the ground as they age. We also cannot definitely predict which players will be able to improve their passing and transition to becoming a more pro-style quarterback like Mcnair and Mcnabb. Quarterbacks that are not able to make that switch may soon enough find themselves out of a job. Therefore, we will now measure the lifespan of mobile quarterbacks through the relationship between career length and rushing ability.

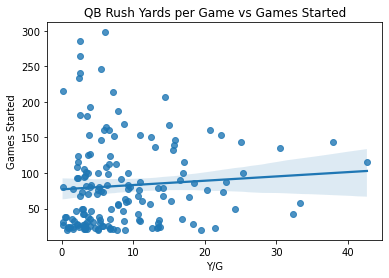

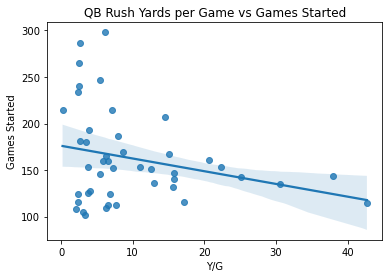

These graphs look at the relationship between quarterback mobility, measured by rushing yards and attempts per game, and career length, measured by the number of games started. This graph has data from retired quarterbacks beginning in 1985. We are looking solely at retired players so that the low starts from those that are just beginning their careers does not sway the data. We also avoided players before 1985 so that our data reflects a style of the game that is similar to the modern one. We are also only using quarterbacks with at least 20 starts to exclude temporary starters for injured QB1s. When looking at the plots, we see no strong negative relationship between games started and rushing yards or attempts per game. We cannot conclude that quarterbacks that run more have reduced longevity. We can, however, see that the points at the top of the graph, which represent players who have started the most games in NFL history, are almost entirely on the left. This means that when looking at players with the longest careers, immoble quarterbacks top the list. Using this as intuition, we replotted our data looking only at QBs with over 100 starts. This criteria selects for franchise quarterbacks, which are generally the type of quarterbacks that GMs are looking to sign and/or draft.

This plot has a somewhat negative trend, however even this relationship is not extremely strong. Qualitatively, our takeaways are limited to state that quarterbacks with the longest careers are most likely to be pocket-passers. Still, it is difficult to observe a correlation between mobility and longevity.

Conclusion

While we can see that dual-threat quarterbacks tend to have their best rushing seasons at younger ages and that quarterbacks with the longest careers are pocket-passers, it is difficult to find any relationship between how mobile a quarterback is and how frequently they actually get tackled or hit. Pairing this with the lack of correlation between starts and rushing volume, we cannot definitely state that the longevity or effectiveness of a dual-threat quarterback will be much worse over the length of their career than a pro-style one. Perhaps we can use McNabb and Mcnair as ideal models for mobile quarterbacks that are able to adapt to age and injuries. Ultimately, the ability for a mobile quarterback to play well from the pocket is a key attribute that all coaches should be looking for. When looking at Anthony Richardson and other uber-athletic Quarterback prospects, this is surely something that GMs are aware of.

Next Steps

The next steps would be to see how specific injuries common among quarterbacks affects their ability to scramble and make plays with their legs. This could be useful to better analyze Lamar Jackson’s contract debate as well as the debate regarding whether taking a mobile quarterback is too great of a risk for a franchise.

Comments