How Deserving Are NBA MVP Selections?

- Bruin Sports Analytics

- Dec 17, 2020

- 23 min read

By: Dean Jones and Vishal Narayan

Introduction

Since the 1955-56 season, the National Basketball Association Most Valuable Player Award has sought to honor the best performing player of the regular season. Every winner eligible for the Hall of Fame has been inducted. Triumphantly punctuating a career year with the Maurice Podoloff Trophy is a dream of basketball players around the world and often a fiercely competitive race among whoever is dominating the league at the moment.

It’s no secret, though, that the rightful winner of the NBA MVP Award has been hotly debated throughout the decades. While Michael Jordan ended his amazing career with 5 such honors, he could have had at least 7 and his most fervent fans remain steadfastly bitter about the 1990 and 1997 selections. Recently in 2020, runner-up LeBron James was denied his own 5th MVP award and shared he was "pissed off" by the media seeming to take his greatness for granted. And many of the top players in the NBA's storied history never won, including greats like Jerry West, Isiah Thomas, and Dwayne Wade. The choices for basketball's highest individual honor aside from the Finals MVP have consistently raised questions among basketball fans as to the legitimacy of the selection process.

It’s not always a polarized debate, however. In some years the eventual winner has blown away all competition, as with Shaquille O'Neal in 2000, LeBron James in 2013, and Steph Curry in 2016. In others there have been two or even three players at the center of the contest, but the winner is named usually due to one deciding factor that proves too compelling for voters to ignore. Russell Westbrook was undoubtedly awarded MVP over James Harden in 2017 because of his historic triple double average despite only winning 47 games. Derrick Rose became the youngest player to win it in 2011 after leading the Chicago Bulls to a league-best 62-20 record, defeating Dwight Howard. The undersized Allen Iverson overcame the towering Tim Duncan in 2001 by leading the league in points and steals.

To really understand the motivations behind the true annual winner of this prestigious award, we’ll have to consider MVP contenders on a case-by-case basis. We decided to only consider the years starting from 1980-81, when the award voting switched to media from players, as this is the contemporary process for selecting MVPs. We also assumed that while the voting process may be subjective and flawed, it's still a relatively good indicator of who the top players are in the league that season. However, the more controversial picks (which we label as having a voting share disparity of 15% or less for the top two players) are sufficiently intriguing to be worth delving into.

Comparing the votes throughout the years, our resulting list of years was the following:

1982: Moses Malone, Larry Bird

2002: Tim Duncan, Jason Kidd

As can be observed from the list and comparing the top three players' voting shares each season, the MVP race has largely been a two-man race in competitive years, but 1990 and 1999 stand out for the presence of a third legitimate contender.

Our ensuing discussion will take into account individual statistics, team performance, and external narratives. We will compare players' individual regular-season performance through points, rebounds, assists, efficiency, steals, blocks, and win shares. Team performance is determined by wins, how many teammates were selected for the All-Star Game, and coaching strategy. Finally, external narratives are tougher to pinpoint, but media perceptions of players at the time and any relevant off-court incidents are mentioned if we believed these played a role. Taking all of these factors into account, we finally offer our opinion of the MVP selection as one of three categories: the MVP was deserving (Satisfactory), the race remains too close to judge definitively (Tossup), or a runner-up should have been chosen (Unacceptable).

Without further ado, here are our takes.

1981-82: The Beginning

Media voting in the NBA was inaugurated with a heated race between Julius Erving and Larry Bird in 1981. Despite a record 30 players receiving MVP votes, ultimately it came down to these two men.

Dr. J's 76ers and Bird's Celtics both ended up with an identical 62-win record that season. Boston enjoyed more All-Star output with Nate "Tiny" Archibald (14/8/2) and Robert Parish (19/2/10) compared to only Bobby Jones (14/3/5) in Philly. From that standpoint, Erving's role in his team's success could be considered more impressive.

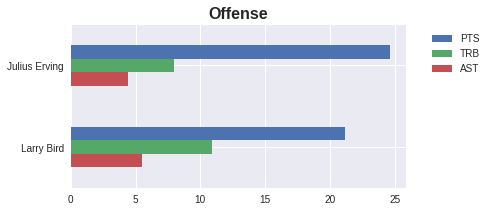

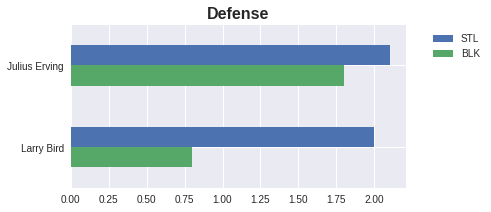

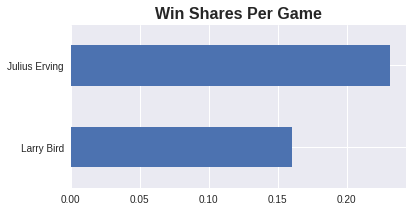

Neither MVP candidate led the league in scoring that season (that honor belonged to Adrian Dantley with 30.7 points per game), but Erving's rate of 24.6 points per game outpaced Bird's 21.2. Bird snagged more rebounds and slightly more assists. His efficiency exceeded Erving in threes and free throws but lagged in field goals. Both averaged the same number of steals, but Dr. J was a stronger presence with blocks. Finally, Erving contributed significantly more win shares than Bird.

It is easy to understand why this MVP race was essentially a tossup, but we understand how Erving's edge in key categories (points, FG percentage, win shares) pushed him over the top with the media. An additional factor that may have unfairly played into his favor was his extensive experience as a seasoned vet, having won the MVP award for the previously operational American Basketball Association thrice, establishing him firmly as a prominent talent compared to Bird's relatively unknown status as a sophomore newcomer at the time. Nevertheless, we do not feel there is compelling statistical evidence Bird was robbed per se; rather, both players would have made worthy selections.

Final Judgment: Tossup

Larry Bird once again fell short in 1982 when Moses Malone won in a shocking turn of events.

Malone's Houston Rockets were kept afloat by his brilliance but only just, as they finished with the West's 6th seed and a 46-36 record. Meanwhile, Bird and the Boston Celtics achieved a terrific 63-19 record to claim the East crown convincingly.

Once again, Bird was well-supported by Nate Archibald (13/8/2) and Robert Parish (20/2/11) both joining him to represent Boston in the All-Star Game. The struggling Rockets did not send any player besides Malone, but Elvin Hayes (16/2/9) and Robert Reid (13/4/7) were a couple bright spots on the roster.

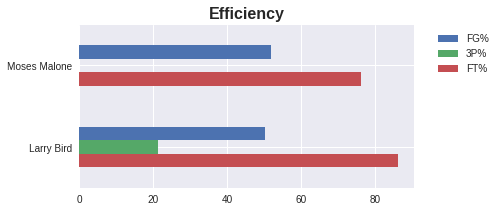

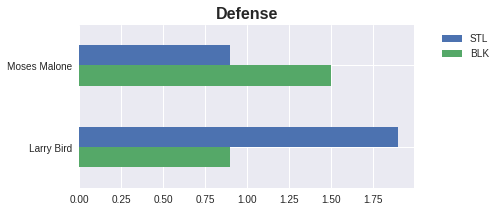

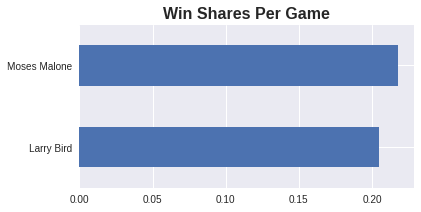

Malone was 2nd in the league in scoring with 31.1 points per game, far outpacing Bird's 22.9 yet most likely due to the Celtics' superior players sharing the scoring load. Bird picked up an impressive 10.9 rebounds per game but Malone was better with 14.7. Bird was a more effective playmaker with 5.8 assists per game. He also had more steals with 1.9 per game while Malone was forceful inside with 1.5 blocks per game. In terms of efficiency, both players were around the 50% mark for field goal percentage. It is no graphing error though that Malone ended up 0% from 3; this statistic serves as a bracing reminder of just how different today's era and requisite qualifications of MVP-caliber players are. Bird meanwhile shot better from the free throw line at 86.3% and actually converted his 3-point attempts - albeit at only 21.2%. In terms of win shares, Malone displayed a small advantage.

The gaudy numbers of Malone, especially in points and rebounds, were no doubt impressive, but awarding the MVP to a player for a team that was not even in the top 5 of its conference is a bit questionable. Malone may have been essential for his team's survival, but Bird transformed the Celtics into a powerhouse with his arrival. He improved the Celtics' record by 32 wins to 61-21 his rookie season in 1980, then improved a bit to 62-20 in 1981, and somehow again raised the bar with 63-19 in 1982. While the media may have still been playing the wait-and-see game with Bird in 1981 when they chose Julius Erving for MVP, his continued dominance and the team's excellence should have been resounding enough for them to recognize him as the best player that year. If the Rockets and Celtics weren't separated by a 17-win disparity, our feelings might be different. But Bird played incredibly, induced excellence around him, and should have won.

Final Judgment: Unacceptable

1989-90: Magic Tricks?

The 1990 NBA MVP race was perhaps the greatest and most dramatic, so we'll delay discussing 1989 until after.

Of the 13 players that received MVP votes that year, 12 have since entered the Hall of Fame. Guys like Larry Bird, Karl Malone, Hakeem Olajuwon, Isiah Thomas. Yet ultimately, 1990 should be remembered best as one of the only true 3-horse MVP races. Charles Barkley received the most first place votes that year, was named to the All-NBA First Team for the third consecutive year and earned his fourth All-Star selection, and lost. Michael Jordan led the league in scoring, made his fourth All-NBA First Team and sixth All-Star Game, and lost. Edging both Barkley and Jordan, Magic Johnson won narrowly for the 3rd time.

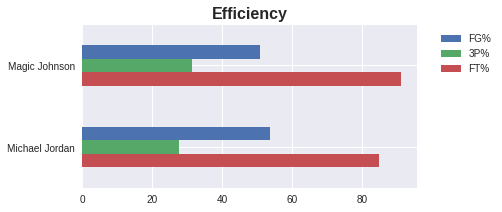

To give Magic his proper due, it should be noted that he played his first year without Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and still led the Lakers to a league-best 63-win record. Magic also suited up in every position that season, demonstrating his immense versatility and mastery of the game. His numbers were also virtually the same as his MVP season prior, with his greatest improvement in 3-point percentage rising from 31.4% to 38.4%.

But the talent the Lakers enjoyed, even with Kareem's departure, was significant. Two All-Star starters in James Worthy (21/4/6) and Byron Scott (16/4/3) were luxuries neither Charles Barkley on the 76ers and Magic Jordan on the Bulls enjoyed. (We didn't forget Scottie Pippen, but he only made his 1st All-Star team that year.) Despite still lagging behind the Lakers, the 76ers' 7-win improvement to 53 wins and Bulls' 8-win improvement to 55 wins over the previous year were significant accomplishments directly attributable to Barkley's and Jordan's will to transform their respective organizations.

And peering deeper into individual stats, it's hard to argue that neither Barkley nor Jordan performed at a higher level than Magic.

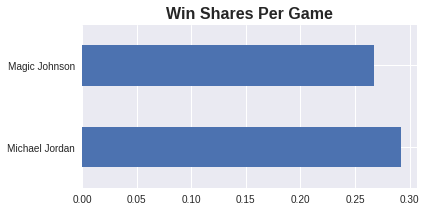

Johnson's 22.3 points-per game lagged Barkley's 25.2 and was absolutely blown away by Jordan's torrid clip of 33.6. He was massively outrebounded by Barkley. His efficiency exceeded Barkley's but only matched Jordan's, who was producing at a higher rate. His defensive stats were outshadowed by both and, in win shares per game, he was once again bested. Slight discrepancies in some categories can be dismissed. But MJ and Barkley both seemed to do more or about the same with less, and should the MVP award not recognize that?

The question of why Magic earned the sport's highest honor is complex. Perhaps the media's perpetual spotlight on LA and its Lakers paved the way. He most likely benefited from the sheer competitiveness not witnessed before in the award's history, as many voters would note that they were unsure how to rank players until the moment ballots were cast. And finally, some will respond with the compelling point that the MVP ending up with the best player on the best team that season is a pretty good decision.

But in 1990, Barkley and MJ both took their team records and individual games to new heights and were outright robbed.

Final Judgment: Unacceptable

Magic's 1990 win was unfortunately reminiscent of his win the year earlier over MJ.

In 1989, Jordan had once again exploded in points per game, with his 32.5 easily exceeding Magic's 22.5. The players produced at similar efficiencies, so just as in 1990 Jordan's higher output particularly shines. His All-NBA Defensive performance dominated Magic's already solid numbers and the win shares advantage once again went to him.

Bear in mind that in 1989, Jabbar was still reliably contributing in LA while Pippen was still developing into... Pippen. The resistance of voters to acknowledge MJ is more difficult to understand with our hindsight bias knowing of Jordan's 6 championships, eventual 5 MVP awards, and the plethora of other well-deserved and hard-earned accolades accumulated over the years. But finally one can point to a lingering, hard-set rationale: win record. The Lakers' 57 wins were best in the West and so Magic basked in a flattering light, while the Bulls' relatively paltry 47 wins landed them at 6th in the East and raised concerns about whether MJ was truly a winner or just a stats machine (surprisingly, almost reminiscent of Russell Westbrook perceptions).

Regardless of one's feelings if the MVP award should be dedicated solely to individual excellence, team success, or some harmonious combination of both, Magic's back-to-back wins remain tough to accept. Our verdict? 1989 can plausibly belong to Magic - although Jordan probably should have won.

Final Judgment: Tossup

1997 and 1999: The Infamous and The Classic

Considered by many basketball fans to be among the worst MVP choices in history, Karl Malone's selection over Michael Jordan in 1997 remains intensely controversial. (For his part, Jordan further revived conversation around this topic on the "The Last Dance" when he revealed losing the award motivated his performance in the Bulls' 4-2 Finals win over Malone's Jazz.) With both players ending up with over 80% of the vote, a distinction only approached by the 2005 race, clearly the choices were polarizing.

Malone led Utah to its best record in team history with 64 wins, best in the West and a remarkable 9-game improvement from the previous year's finish. Jordan and Chicago could not quite match their 72-win 1996 season, the best in league history until the Warriors' 2016 73-win total, but still finished with 69 wins to win the East in 1997. Scottie Pippen (20/6/7) had blossomed into an All-Star starter and landed multiple All-NBA and All-Defensive First Team honors. John Stockton (14/11/3) also started in the All-Star Game by playing excellently for the Jazz, especially excelling in assists, and having picked up All-NBA First Team and All-Defensive Second Team honors previously. Utah and Chicago thus presented potent 1-2 punches for opponents.

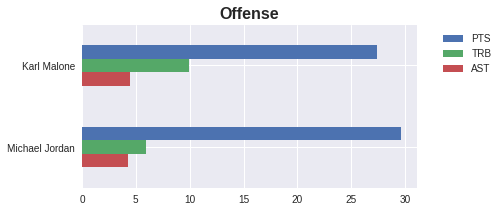

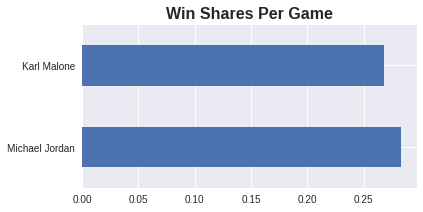

MJ's 29.6 points per game narrowly outdid Malone's 27.4, while Malone displayed a strong command inside with rebounding. Assists, steals, and blocks were virtually equal. Malone's field goal percentage of 55% was substantially higher than MJ's 48.6%, presumably due to closer shot selection. Jordan showed greater mastery from distance at 37.4% from 3 and 83.3% from the free throw line. Finally, Jordan also showed a slight edge in win shares per game.

Both players played phenomenally, but when it really comes down to it, you cannot help but feel Jordan was a bit more deserving. Jordan had actually won the award a year earlier with only marginally superior numbers in the legendary 72-win 1996 season, which ironically perhaps led to his downfall in 1997. The widespread perception that voters were tired of voting for Jordan after 4 previous wins, just as they have refrained from crowning LeBron James in recent years, cannot be definitively verified but seems particularly credible. Jordan was not competing against Malone; he was rather competing against himself.

Final Judgment: Unacceptable (slightly)

In the 50-game 1999 lockout-shortened season, MJ no longer competed against anyone. Jordan had announced his (second) retirement on January 13th before play began, and so Malone found himself contending with Alonzo Mourning and Tim Duncan in only the second and last true 3-way MVP race to date.

Mourning led the Heat to top the East with 33 wins, while Duncan's Spurs and Malone's Jazz finished with an identical 37 wins. Malone was a favorite for most of the year, but Mourning's career year and the Spur's rebound from early struggles - and Duncan's outplaying of Malone in late season head-to-head matchups - tightened the race to a nail-biting finish down the stretch.

One of the many consequences of the owner-induced lockout was the cancellation of the All-Star Game in Philadelphia for the first and only time in NBA history. Tim Hardaway (17/7/3) in Miami, David Robinson (16/2/10) in San Antonio, and John Stockton (11/8/3) in Utah could have all joined Mourning, Duncan, and Malone in an alternate reality where the game was played (with all 3 top MVP candidates locks to play of course).

Malone's clip of 23.8 points per game was a decline from previous years and trailed Allen Iverson's league-leading 26.8 but was enough to edge out Mourning and Duncan. All 3 big men were excellent on the glass, with Duncan leading them at 11.0 rebounds per game. Finally, Malone excelled in assists over Duncan and Mourning. In terms of efficiency, Mourning nosed out Malone and Duncan in field goal percentage at 51.1%. The only "capable" 3-point shooter was Duncan at 14.3%, as Malone and Mourning could not get a single shot from afar to fall. To be fair, less games equals less attempts, but the numbers are still ugly. Mourning averaged a monster 3.9 blocks per game, while Malone led in steals. Finally, Malone showed a sizable advantage in win shares per game.

The top 3 choices were rock-solid, if not as spectacular as Michael Jordan. No fan could have expected them or anyone else to be so soon after the (arguable) GOAT's departure. The race was the thriller it should have been. Despite the now 35-year old Malone's regression from his career peak, his 1999 win is not as dubious as 1997. Persuasive arguments in favor of Mourning and Duncan could most definitely be constructed, but with all candidates playing at a comparable level, the final outcome cannot be too harshly criticized.

Final Judgment: Tossup

2002 and 2003: Dunkin'

Tim Duncan would not have to wait long after his close 1999 loss to win MVP, defeating Jason Kidd in 2002 in hugely controversial fashion.

Kidd arrived in New Jersey after a trade from the Phoenix Suns during the 2001 offseason and arguably transformed the franchise. With the electrifying point guard at the helm in 2002, the Nets doubled the previous year's 26 wins to finish with 52 wins and fully shed their status as league cellar dwellers to win the East. Duncan led San Antonio to 58 wins, an identical finish from the year prior, but behind the Sacramento Kings' 61-win record in the West.

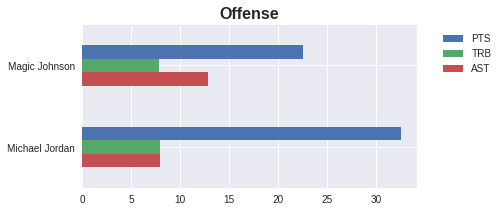

Kidd's playstyle was perhaps unconventional for media accustomed to MVP candidates dominating the league in scoring - including Duncan with a strong 25.5 points per game - but perfect for unearthing New Jersey's potential through a balanced, free-flowing offensive attack. The leading scorer was not Kidd but Kenyon Martin at just 14.9 points per game. Keith Van Horn contributed 14.8. Kidd was third at 14.7. Yet no one in the league doubted the Nets were Kidd's team, with his defensive intensity and playmaking elevating his teammates' play and none but him making the All-Star Game.

Duncan was quietly excellent for the Spurs, leading the NBA in field goals, free throws, and rebounds. His goal to have the best season of his career and win the MVP carried through on the defensive end, where San Antonio ranked among the league's best. While Duncan was the team's lone representative in the All-Star Game, he was irrefutably foundational to establishing a culture of greatness in Alamo City.

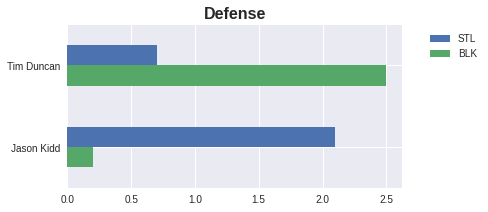

Comparing individual stats for such fundamentally different players does not help much with determining who was more deserving of the award but further illuminates the distinction in playstyles. As discussed earlier and can be clearly observed, Kidd dramatically lagged behind Duncan in points due to the divergence in New Jersey's and San Antonio's offensive approaches. Duncan also posted prolific rebounding numbers at 12.7 per game, though Kidd was similarly exceptional in assists at 9.9 per game. By virtue of his role as the Spurs' premier offensive weapon, Duncan claimed a considerable field goal percentage advantage at 50.8%, yet Jason Kidd was slightly more efficient from the free throw line and actually an okay 3-point shooter at 32.1%. The defensive comparison is almost laughable, as Duncan was elite in blocks at 2.5 and Kidd in steals at 2.1 but neither fared so well in the other category. Finally, Duncan claimed far more win shares, but Kidd's impact was most definitely underestimated due to his relatively low points per game. Kidd's true impact on winning can clearly be seen in his team's legendary turnaround.

An external, off-the-court factor is almost certain to have played into ballots. In January 2001, Kidd was arrested for domestic violence assault against his current wife Joumana Samaha and eventually plead guilty to spousal abuse, leading to a $200 fine, mandatory anger management training, and the trade to New Jersey.

Whether the MVP award should solely be determined by on-court performance or not is debatable, but Kidd's character issues complicated voting for him and Duncan stood to gain with a pristine image and well-known identity as an especially conscientious if slightly boring individual. Based on the hardwood alone, Kidd should have won for almost single-handedly changing the Nets' culture, but you cannot fault the media for turning to another player with a magnificent season.

Final Judgment: Tossup (but close to Satisfactory)

Duncan repeated as MVP in 2003 in a close yet far less contentious race with Kevin Garnett.

Garnett led the Minnesota Timberwolves to 51 wins, a 4th place finish in the West. Duncan paced the San Antonio Spurs to 60 wins, just barely claiming the top seed in the West from the 59-win Sacramento Kings and 60-win Dallas Mavericks.

None of Garnett's or Duncan's teammates made the All-Star Game. For the Spurs, sophomore point guard Tony Parker (16/5/3) and Italian league import Manu Ginobili (8/2/2) were still developing, while Stephen Jackson (12/2/4) was also a key contributor. The Timberwolves depended on Wally Szczerbiak (18/3/5) , Troy Hudson (14/6/2), and Rasho Nesterović (11/2/7) to attack opponents in a variety of ways.

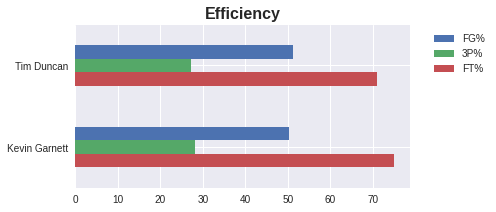

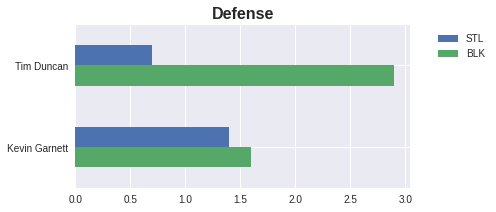

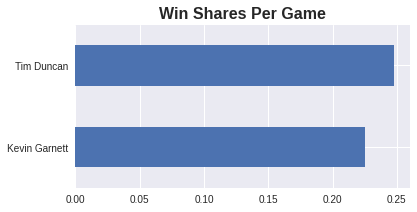

KG and Duncan averaged a double-double and were practically equal in scoring and rebounding, with Duncan's 23.3 points per game and Garnett's 13.4 rebounds per game setting the edge. Neither actually led the league though; Tracy McGrady and Kobe Bryant both averaged around 30 points per game, while Ben Wallace averaged a ridiculous 15.4 rebounds per game. KG produced more assists at 6.0 per game. In terms of efficiency, the players were again almost identical at around 50%, 27% and 70% for field goals, 3s, and free throws respectively. Both men were formidable defensively - Duncan with almost 3 blocks per game and KG with 1.4 steals per game. Finally, Duncan picked up more win shares.

While the players had very similar seasons in terms of individual performances, the defending champion Spurs had a better season. San Antonio's superior team success in comparison with Minnesota ultimately proved decisive for the media to select The Big Fundamental.

Final Judgment: Satisfactory

2005 and 2007: New Places, Old Faces

Yet another still hotly debated MVP selection from the 2000s was made with Steve Nash over Shaquille O'Neal.

Nash was originally drafted by the Phoenix Suns in 1996, playing two seasons with them before being traded to the Dallas Mavericks and developing into an All-Star and All-NBA Third Team player. However, Dirk Nowitzki's excellence prevented Nash from taking a truly central leadership role, leading the point guard to return to Phoenix for the 2005 season.

Shaq was drafted first overall by the Orlando Magic in 1992, more than living up to lofty expectations. Leaving in 1996 after contract talks broke down, O'Neal joined the LA Lakers and earned Finals MVP honors for the 2000-2002 championships. But in 2004, his enduring feud with Kobe Bryant led him to return to Florida, now a Miami Heat.

Like Jason Kidd's impact on the New Jersey Nets in 2002, Nash's arrival in Phoenix in 2005 led the Suns on an incredible turnaround from 29 wins the previous season to a league-best 62 wins, earning the West's top seed. The extent of Nash's impact could be seen when his brief absence due to a thigh injury led the team to lose 6 straight games after starting the season 31-4. Mike D'Antoni also was key to maximizing the talents of Suns' roster in his first year coaching the team, with high-volume three-point shooting and ball movement flourishing by virtue of 2002 rule changes penalizing hand check fouls on the perimeter.

The Miami Heat also finished first place in their conference, with a 59-win record a noticeable if not quite as dramatic improvement from the previous year's 42 wins. Shaq joined an excellent Dwayne Wade and Stan Van Gundy both in their second years and formed a productive partnership for cultivating the Heat's potential.

Shaq was joined by Wade (24/7/5) in the All-Star Game. The two would enjoy a more harmonious partnership than Shaq-Kobe en route to becoming one of the most dangerous duos in basketball. Meanwhile, the Suns' philosophy led two more players to join Nash - Shawn Marion (19/2/11) and Amar'e Stoudemire (26/2/9) - in terrific seasons. Miami was more top-heavy than Phoenix directly due to the team's fundamentally different superstars.

Comparing stats for a point guard and center can only tell us so much once again, but we'll still analyze this information for its worth in highlighting the contrasting styles ahead of voters.

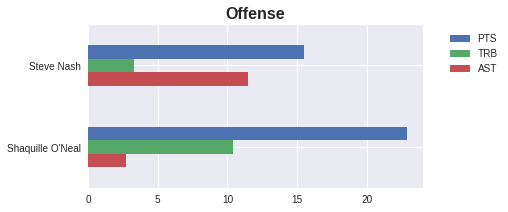

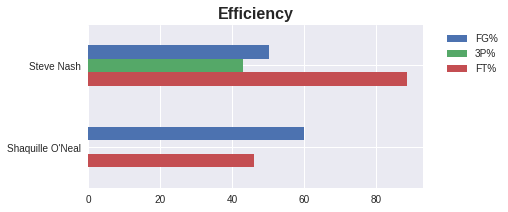

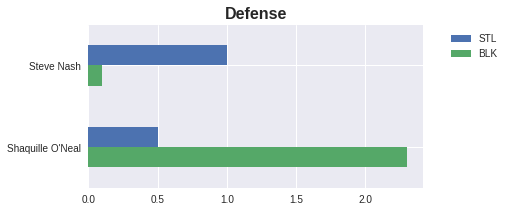

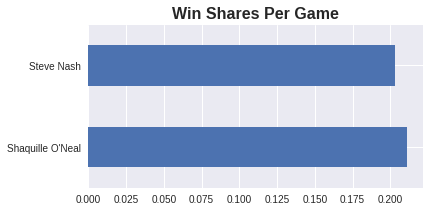

Shaq outscored Nash by a wide margin, 22.9 to 15.5 points per game. He also was a dominating force on the glass with 10.4 rebounds per game. Nash demonstrated his central role in the team's success with a league-leading 11.5 assists per game. In terms of efficiency, there's a reason Hack-a-Shaq became a popular if inconsistently effective strategy in the league. While O'Neal converted a spectacular 60.1% of his field goals, he was a woeful 0% from 3 and 46.1% from the line. Nash was 50.2%, 43.1% and 88.7%, narrowly missing out on his first 50/40/90 season. On defense, Shaq wreaked havoc with 2.3 blocks per game while Nash could be disruptive with 1.0 steal per game. With regard to win shares, both players were about tied.

O'Neal represented size, physical dominance, and old-school toughness, while Nash offered glimpses of the future with efficient distance shooting and whiplash-inducing passes. In the end, Shaq's individual greatness was acknowledged but determined less impressive than Nash's role in catalyzing the Suns' tremendous regular-season run to finish atop the league. Some may say that unlike Kidd, Nash had Stoudemire producing at an incredible clip and D'Antoni joining the team to immediately earn Coach of the Year. Yet the midseason six-game losing streak for the Suns stands out. Nash missed four of those games and clearly was not himself in the other two. His +18 performance in a battle with the Heat right before the rut and his 30-point performance to snap Phoenix back into the win column against the Nets serve as convincing evidence of his impact. Thus, we're inclined to assert that Shaq may have posted more dazzling stat lines, but Nash made an equally compelling case for guiding his team to the top of the league. Either could have won the award.

Final Judgment: Tossup

In 2007, Nash found himself falling short against his former teammate, close friend, and MVP rival, Dirk Nowitzki. While found worthy of winning the award back-to-back from 2005-06, the task of convincing voters to send him to the exclusive threepeat club of Bill Russell, Wilt Chamberlain, and Larry Bird ultimately proved too difficult. (Yep, neither MJ nor LeBron have done it, so there's some consolation for Nash in that.)

The Dallas Mavericks and Phoenix Suns were the two best teams in the West in 2007. Nowitzki's Mavericks had a historic 67-win season, while the Suns were close behind with 61 wins. Both teams achieved impressive win streaks of 17 games. In a late regular-season matchup in Dallas, the two MVP candidates played exceptionally well with 30-point games (although Amar'e Stoudemire was actually the leading scorer with 41 points). The double overtime thriller ultimately ended with a Suns' 129-127 victory.

Just as in 2005, the Suns' core trio of Nash, Stoudemire (20/1/10), and Shawn Marion (18/2/10) made the All-Star Game. Nowitzki was joined by Josh Howard (19/2/7) for Dallas.

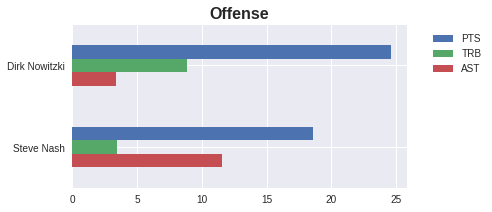

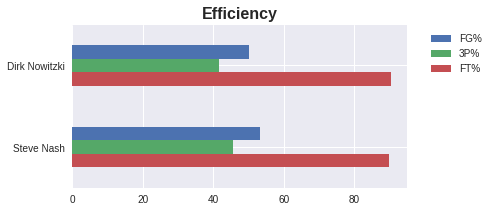

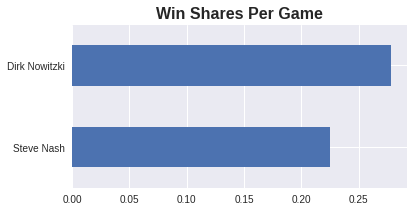

Nowitzki's 24.6 points per game exceeded Nash's 18.6. His rebounding (8.9 per game) was excellent, while Nash displayed his offensive mastery through his league-leading 11.6 assists. Neither player was a monster defensively, but Nowitzki almost averaged a block per game and was close to Nash's steal rate of almost one per game. Finally, Nowitzki established a solid win shares cushion over Nash.

Nash's numbers were almost identical to his 2006 MVP season, which helps explain the race's tight finish. However, the prospect of voting Nash to his third straight MVP award ultimately was too tough to stomach for many in the media when the point guard had never posted the most tremendous stat lines. Another factor Dirk Nowitzki could take credit for was the Mavericks having the best record that year - 7th-best in league history. The Mavs' later shocking playoff elimination by the eighth-seeded "We Believe" Warriors was also historic for the wrong reasons and may cast more controversy over the selection today, but the award is based on regular-season performance and Nowitzki was the best player on the best team. He was deserving.

Final Judgment: Satisfactory

2017: Westbrook in Isolation

Russell Westbrook had a historic season averaging a triple-double in 2017, but many of today's fans heavily argue whether he was truly more deserving than James Harden. Westbrook's recent playoff struggles and questionable decision-making have only amplified his detractors.

It is true that Westbrook leading the Oklahoma City Thunder to 47 wins and only the 6th seed in the West was not an achievement heavily synonymous with MVP recognition. (Only Moses Malone in 1982 won while also capturing the 6th seed in the West.) Kevin Durant's departure to the Golden State Warriors, however, explained the Thunder's struggles and thus Westbrook's outstanding individual stats shined as the reason OKC even made the playoffs at all.

In contrast, Harden's Houston Rockets won 55 games and were the West's 3rd seed, buoyed by a 14-game improvement over the previous season. Mike D'Antoni's arrival as head coach, along with Ryan Anderson, Eric Gordon, and Nene, and the decision to move Harden to the point guard position worked out well. D'Antoni and his trademark offense, living and dying by the 3, leveraged the roster's talents, most of all Harden.

With the Warriors sending four players to the All-Star Game, spots on the Western Conference All-Star Team were limited and only Harden and Westbrook were able to make it for their respective franchises. Victor Oladipo (16/3/4), Steven Adams (11/1/8), and Enes Kanter (14/1/7) helped round out OKC. Gordon (16/3/3), Trevor Ariza (12/2/6), and Anderson (14/1/5) were some crucial pieces on a deep Houston team.

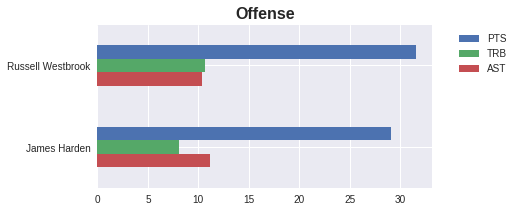

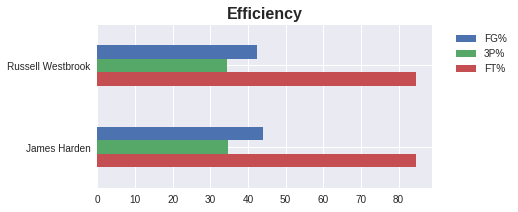

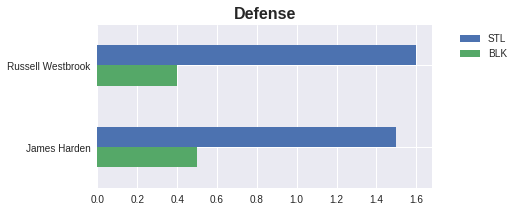

Westbrook led the league in scoring with 31.6 points per game, while Harden was close behind at 29.1. Harden had a league-high 11.2 assists per game with Westbrook at 10.4. Westbrook was a slightly better rebounder with 10.7 per game. Harden held very slim edges in efficiency across the board, at 44.0%, 34.7%, and 84.7% for field goals, 3s, and free throws respectively. The players had nearly equivalent defensive stats, about 1.5 steals and 0.5 blocks per game. Harden contributed slightly more win shares than Westbrook as a result of the win disparity between Houston and OKC.

With both players having extremely similar numbers but Harden winning more regular-season games, the MVP award could very well have gone to him instead of Westbrook. However, the case for Russ was helped by his historic feat of averaging a triple-double over the entire regular season, an accomplishment previously only claimed by Oscar Robertson way back in 1961. He also broke Robertson's single-season record of triple doubles by notching 42 of them. In those games, the Thunder went 33-9; in the others, just 13-25, demonstrating his importance in the team's success. In addition, Durant joining the Warriors and becoming the league villain led people to want Westbrook to succeed. When he took his game to extraordinary heights, it made sense to award him MVP.

While we wish Harden did not have to be denied, Westbrook was ultimately most deserving.

Final Judgment: Satisfactory

Conclusion

Analyzing the most controversial MVP races since the 1981 change to media voting led us to develop a better understanding of the criteria voters feel that the vague "most valuable" distinction depends on. While 11 of the past 30 years' selections were decided by less than 15% of the voting share separating the top two players, every year was undoubtedly unique. Our personal feelings about the final decisions' correctness encompassed a wide range. Here's the full breakdown: Satisfactory

Tossup

Unacceptable

Our resulting determinations, only expressing outright disapproval with 4 of 11 selections, suggest that the NBA MVP voting process mostly works out correctly. However, it is important to keep in mind that we did not consider every year and there is no metric that could objectively determine who most deserves the award. Even with our rigorous individual comparison combined with contextual knowledge of team performance and player narratives, many basketball fans will likely still argue about at least one race or another. For example, Bleacher Report's ranking of controversial races included Steve Nash's back-to-back 2005-06 selections and Derrick Rose in 2011, while CBS Sports released their own rankings including Allen Iverson in 2001 and Kobe Bryant in 2008. We may very well have reached the same conclusions about Iverson, Rose, and Bryant if we considered these races, but we also could have felt very differently and included years not yet mentioned for our own definitive list.

Ultimately what it takes to win MVP is a moving target. Stephen Curry may have won back-to-back MVPs and his unanimous selection in 2016 will rightfully go down in history, but the GOAT conversation centers around Michael Jordan, LeBron James, and Kobe Bryant despite those players never receiving that honor. Being the league's best player is not enough, as a terrific year from another player can be deemed more impressive. Winning matters, as evidenced by the abundance of awards going to players on teams with the 1st, 2nd, or 3rd seed, so being the best player on the best team is a great position to be in. But Russell Westbrook and Moses Malone on 6th seeded teams both proved that is not the only consideration; stellar individual performance keeping a team alive in the playoff picture could be rewarded. Conversely, Steve Nash and Jason Kidd both took a bottom-feeder team to the NBA's top echelon with their free-agency arrivals and greatly impressed those in the media, despite not posting as ridiculous numbers as their competitors. This inconsistency has contributed to some confusion and heated debate among fans. With Giannis Antetokounmpo's recent "don't call me MVP" comments, the importance of playoff success is even growing for fans - although there is no indication the media will take that into account. For the record, the MVP is a regular season award and should be based on regular season performance alone.

But do we really want the MVP selection process to be rigidly uniform? Would we really want LeBron James to win each year or the award to automatically be granted with the top seed? Our obsession with best tends to be distracting, preventing us from appreciating players who did not win the championship or leading us to vilify an MVP to strengthen the case for our preferred selection. While we do feel grievous mistakes have been made, it is important to recognize that the inherent uncertainty and flawed nature of the award helps make the annual race so intriguing when multiple players are legitimate contenders. Debates can be productive if respectful, as meaningful dialogues intended to highlight the pros and cons of different choices and not a war of words on Twitter. We can recognize that winning an MVP award is indeed a tremendous accomplishment, but not all-consuming to the point that other players and their fans should feel like losers.

After all, Giannis could tell you a bit about that.

Comments